Introduction

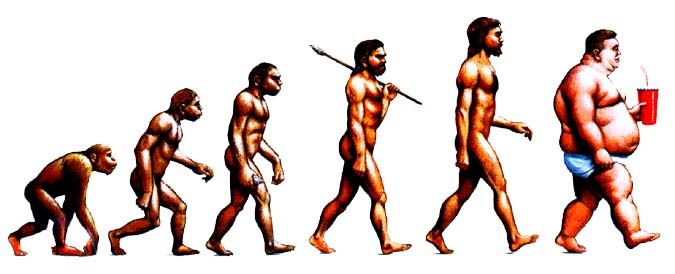

How has evolution favored obesity? As the obesity epidemic becomes more and more prevalent (with upward of two-thirds of Americans being overweight or obese), this question becomes more and more imperative (King, 2013). Eating behaviors are a complicated and multifaceted domain, and are shaped by many different influences. Some of these include evolution, genetics, emotions, and environmental factors (Weltens, Zhao, Oudenhove, 2014). Shockingly, Kardum et al. (2008) state that 312 million of the world’s people are obese. This short blog will touch on evolutionary reward pathways, thrifty genes, and evolutionary adaptation to diet.

Evolutionary Adaptation to Diet

Historically, Paleolithic men required great amounts of high-energy foods and man’s diet contained much more protein and less sodium and lipids than modern man. Currently, the average modern day North American has access to food throughout the whole year with a diet that commonly consists of refined sugars, complex carbohydrates and an excess of fatty-acids. Since this drastic change in diet occurred in just a small fraction of time compared to the time it takes for adaptation to occur, homosapiens, as a species, have yet to evolve metabolically and gastrointestinally to the modern day diet. This historical biological condition lowered people’s metabolism rate and increased their adipocytes (fat storage) for when starvation kicked in, causing mankind to unintentionally store food in their system (Kardum et al. 2008).

Reward Pathways

Eating is generally considered a pleasurable experience, and Berthoud, Lenard, and Shin (2011) speculate that part of the reason eating is so pleasurable is that eating behaviors have acted as an evolutionary driving force that served as a motivator to engage in dietary consumption.

Weltens, Zhao, and Oudenhove (2014) tell us that food, especially fatty food, has obtained intrinsic value throughout human evolutionary history. This intrinsic reward value has been linked to brain reward and hedonic pathways (2014). Dopamine signaling within these areas appears to be a crucial component of modern reward systems (Berthoud, Lenard, and Shin, 2011). King (2012) expresses that humans developed a unique pathway in the cortico-limbic areas of the brain, which evolved to signal preference to high fat and high carbohydrate rich foods.

Put in simpler terms, the innate pleasure of eating and the appeal of carbohydrate and fatty foods evolved through natural selection to provide the motivation required to acquire adequate nutrient and caloric intake when food was scarce (Weltens, Zhao, Oudenhove, 2014). While these reward pathways would have been useful thousands of years ago when humans were primarily hunter-gatherers, modern humans in industrialized countries no longer need to expend much energy to obtain a high calorie meal (King). This signaling, once crucial for survival, now appears to be our nemesis when it comes to resisting the high calorie, high fat, sugary foods that are over abundant in affluent societies (Weltens, Zhao, and Oudenhove, 2014).

Thrifty Genes

John Speakman (2013) argues that the evolution of obesity is mainly due to a genetic predisposition (Speakman 2013). He suggests that there are three explanations for this genetic disposition. First, as obesity was adaptive and allowed us to survive, humans all carried thrifty genes that help store energy as fat. The second explanation is that obesity is not adaptive and may not have existed, but “may be favoured today as a maladaptive by-product of positive selection on some other trait”, which causes obesity due to a variation in brown adipose tissue thermogenesis (Speakman 2013). The third explanation is that many mutations in the genes have been neutral over time and these “thrifty genes” have caused people to become obese.

It is hypothesized that individuals with traits that allowed them to store food as fat when there was a food abundance were better equipped for survival in times of food shortage. Those individuals who didn’t have the ability to store food as fat for energy to use when there was a shortage of food were more likely to die of starvation, and over time, those genes were “selected out” due to natural selection (Andrews P and Johnson RJ 2015). This is where the term “thrifty genes” was coined, and although there has been much debate on the accuracy of the term due to recently conducted studies and an improvement in quality and access to technology, the general idea is still used to generate new hypotheses on the role of genetics in obesity (Prentice AM et al. 2008).

Conclusion

Hopefully, with a better understanding of the brain reward circuitry, thrifty genes, and the evolutionary adaption mechanisms to diet, we will be able to reverse the obesity pandemic. Further research and understanding will hopefully help mankind develop healthy eating habits, work with our unique genetic makeup, and ‘rewire’ our brain circuitry to limit meal size and weight gain before we see more preventable obesity-related morbidity and mortalities.

References

Andrews P, Johnson RJ. 2015. The Fat Gene. Scientific American. [Internet]. [cited 2016 Mar 10]; 313(4): 64-69. Available from: http://eds.b.ebscohost.com/eds/detail/detail?vid=2&sid=0732fa7e-5c85-43c3-afbd-5eed066968fe%40sessionmgr113&hid=112&bdata=JnNpdGU9ZWRzLWxpdmU%3d#db=a9h&AN=109384965

Berthoud, H., Lenard, N., Shin, A. (2011). Food reward, hyperphagia, and obesity.

American Physchological Society. 300(6). DOI: doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00028.2011. Retrived from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3119156/

Kardum I, Gracanin A, Hudek-Knežević J. 2008. Evolutionary explanations of eating disorders. Psychological Topics [Internet]. [cited February 11 2016]; 17(2): 247-263. Available from: http://ezproxy.tru.ca/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=a9h&AN=36784903&site=ehost-live. ISSN: 1332-0742

King, B. (2013). The modern obesity epidemic, ancestral hunter-

gatherers, and the sensory/reward control of

food intake. American Psychologist. 68(2): 88-96. DOI: 10.1037/a0030684

Mcnamara, John M., Alasdair I. Houston, and Andrew D. Higginson. (2008). Costs of Foraging Predispose Animals to Obesity-Related Mortality When Food Is Constantly Abundant. Plos One 10.1. 1-13. Web.

Prentice AM, Hennig BJ, Fulford AJ. Evolutionary origins of the obesity epidemic: natural selection of thrifty genes or genetic drift following predation release. International Journal of Obesity [Internet]. [cited February 11 2016]; 32: 1607-1610. Available from: http://web.b.ebscohost.com/ehost/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?vid=3&sid=192a0ec2-fd88-4c51-bb42-aa71c79c7531%40sessionmgr112&hid=123. Doi: 10.1038/ijo.2008.147

Speakman, John R. (2013). Evolutionary Perspectives on the Obesity Epidemic: Adaptive, Maladaptive, and Neutral Viewpoints. Annual Review of Nutrition 33.1. 289-317. Web.

Wells, Jonathan C. K. (2011). An Evolutionary Perspective on the Trans-generational Basis of Obesity.” Annals of Human Biology 38.4. 400-09. Web.

Weltens, N., Zhao, D., Oudenhove, L. (2014). Where is the comfort in comfort foods?

Mechanisms linking fat signaling, reward, and emotion. Neurogastroenterology & Motility. 24: 303-315. DOI: doi: 10.1111/nmo.12309